Over 900,000 People Dead, a ‘Vast Undercount,’ and $8 Trillion Looted

These are the findings of the Costs of War Project. What would you rather have had for the $8,094 that you, personally, spent on the War on Terror?

Edited by Sam Thielman

BROWN UNIVERSITY’S COSTS OF WAR PROJECT does what the U.S. government refuses to do: It provides thorough accounting for the War on Terror in terms of blood let and money redistributed upward. In their first update of this grim reckoning since 2019, Neta C. Crawford and Catherine Luntz now find that the War on Terror has killed between 897,000 and 929,000 people across five battlefields of its operation.

The Costs of War Project is analytically conservative. Unlike several nongovernmental surveys over the years, it does not conduct epidemiological studies to determine the true lethality of the war – such as deaths from war-shattered public health systems, lack of access to clean water, war-prompted displacement, and other indirect but real consequences of conflict. Instead, the project only counts direct death. The authors acknowledge the shortcomings of this approach.

“The deaths we tallied are likely a vast undercount of the true toll these wars have taken on human life,” said Dr. Neta C. Crawford, the co-director of the Costs of War Project, in a statement accompanying her new data. “It’s critical we properly account for the vast and varied consequences of the many U.S. wars and counterterror operations since 9/11, as we pause and reflect on all of the lives lost.”

These figures include at least 46,319 dead Afghan civilians; 24,099 dead Pakistani civilians – a shocking figure, one that goes far beyond drone strikes – between 185,000 and 209,000 dead Iraqi civilians; 12,690 dead Yemeni civilians; and a staggering 95,000 dead Syrian civilians. When it comes to those Syria figures, remember that on Monday we noted that the U.S. military claims only 1,417 civilians have been killed in Syria and Iraq since the 2014 war against ISIS began.

The Project does not tally the dead in Somalia, which has been caught in the War on Terror since 2006. The project itemizes the death toll across five of the war’s battlefields: Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, “Syria/ISIS,” and Yemen. Those are not the limits of the war: another category, Other, records 1000 deaths. But those battlefields are where comparatively robust records are obtainable, such as they are. Crawford and Luntz, who in my view are performing a public service while shaming the government for shirking its responsibility, have only so much bandwidth and research support.

In Pakistan and Syria, the shocking body count is partially explained by the researchers widening the scope of casualties beyond those caused directly by the United States. Crawford explained in an email exchange that she’s counting deaths caused by all parties in the conflict. As best I understand it, the Costs of War Project is trying to factor out the “counterterrorism” deaths that appear on their face not to be related to the War on Terror – Crawford notes that she’s not counting all Pakistani military deaths in the past 20 years – while maintaining a widescreen focus of all the War on Terror’s dimensions there.

While I was initially skeptical, I’ve come to agree that this wider picture of the conflict is more holistic. In Pakistan, the War on Terror was fought by Pakistani soldiers and intelligence officers as well as by drones. The job of disaggregating these already-inexact statistics creates imprecision.

In Syria, Crawford clarifies that she’s counting deaths after the U.S.’ 2014 intervention. Casualty figures in Syria are subject to considerable dispute. For combatants, the Project relied on frameworks compiled by the Syrian Observatory on Human Rights. Very likely this figure includes deaths caused by Bashar Assad’s forces or their Russian patrons. But it’s also hard to tell where the War on Terror begins and ends in the Syrian civil war.

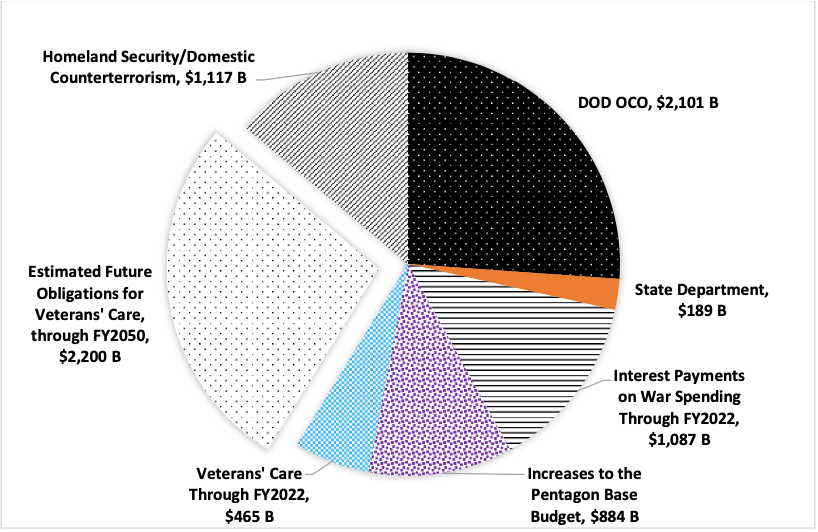

WHEN FACTORING IN ONGOING, SPECIFIC COSTS of the War on Terror, including risibly inhumane medical treatment for veterans, the U.S.’ generation-long – and continuing – war has cost $8 trillion so far.

The Costs of War Project exhumes a study I hadn’t seen: a Pentagon tally, required by Congress, of the cost of the wars in Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan to each U.S. taxpayer. It doesn’t seem to be broken down by actual tax burden, which would highlight how unequally the costs of war are truly borne. Nevertheless, the Pentagon estimated in March that these wars – which are hardly all the operations in the War on Terror franchise – cost you, the American reading this, $8,094 and counting.

What would you rather have done with your $8,094?

Including its Pakistani adjunct, the Afghanistan war cost $2.313 trillion, an especially high price for a defeat indelibly emphasized by a drawn-out Saigon/Benghazi endgame. (That price rises to $3.413 trillion when factoring in obligated veterans’ care.) It killed 2,324 U.S. servicemembers, six Defense Department civilians, 3,917 American contractors – yes, way more contractors than servicemembers – and 1,144 allied foreign forces. (They wouldn’t be tallied here, but add to that the CIA deaths at FOB Chapman in 2009; if you don’t know what that is, it was 187 on an undercover COP.) It killed 69,095 Afghan soldiers and police, a staggering total – multiple U.S. Army corps’ worth of dead Afghans whom the U.S. paid to fight for the regime it built and then derided as inept. If we accept that measuring the line between civilians and what the Project calls 'opposition fighters' is a difficult proposition, then the war killed 99,212 Afghans who either hoped to endure it, or who were compelled to wage it. The war killed 74 reporters trying to cover it.

Remember that these figures, as Dr. Crawford says, are undercounts.

BUT, ASIDE FROM THE TALIBAN, someone won the War on Terror.

Since 2001, the base Pentagon budget – that is, the part of the Pentagon budget that isn’t the wars, but everything else the military does in its resting state – has skyrocketed. The Costs of War Project contextualizes a trend line that hides in plain sight, in literally every Pentagon budget proposal, repeated so often as to be numbing. In 2001, the Pentagon base budget hovered at $300 billion. Today it is comfortably over $600 billion.

“It has now led to normalization and institutionalization of spending in Pentagon’s ‘base’ budget that was previously considered as part of the post-9/11 wars,” Crawford writes, something that has recently “become explicit under the Biden administration,” which eliminated the wartime slush fund known as the overseas contingency operations account (OCO) and funded the wars in the base budget. I’ve attended liberal think-tank panel presentations that discussed funding the wars from the base Pentagon budget as a good-government measure, something that they did not consider ending the fucking wars to be.

Here is what that base Pentagon budget looks like in practice, as patiently summarized by Crawford, who channels the spiral I would go through annually during my years reporting on Pentagon Budget Weeks:

The Department of Defense is not internally consistent or clear about its spending on the post-9/11 wars: spending may shift from one budget to another inside the department, categories may be overly broad, or detailed reporting of a function may entirely disappear. For instance, Operation Noble Eagle, which began in September 2001 as an operation to defend the U.S. air space and bases, was funded in the emergency war budget through FY2004 and switched to the base budget in FY2005. More significantly, the DOD’s own reports of war spending are inconsistent and the basis for accounting is sometimes not fully explained. For example, in the DOD’s March 2021 “Estimated Cost to Each Taxpayer for the Wars in Afghanistan and Iraq,” the DOD reports the annual cost for the war in Afghanistan as $39.676 billion, and $8.892 billion for Iraq and Syria for FY2020. It notes that “Estimated costs for Afghanistan include related regional costs that support combat operations in the U.S. Central Command area of responsibility.” This does not match the total funding as appropriated by Congress for Afghanistan as stated by the DOD’s Comptroller which reports $17 billion and $7 billion respectively for the Afghanistan, and Iraq and Syria, war zones. These two DOD reports differ from each other because they take different categories of functions and operations into account. Neither of these reports’ figures match the DOD’s Office of Lead Inspector General, “COP-OCO: FY 2021 Comprehensive Oversight Plan Overseas Contingency Operations.” There was a more detailed breakdown of costs available from the DOD, but this has apparently not been produced since September 2019, and in any case, this breakdown also does not match other DOD reports. [bolds added]

The thing about the military is it doesn’t make things. It buys things, and it funds things. It buys things from not particularly many people, all things considered, since not many people have the capital necessary to manufacture aircraft carrier hulls or bomber engines. Those who do get obscenely wealthy off a death machine that functions as the American variety of state capitalism. Some of them get to run the Pentagon. It’s been some of the greatest times of their lives, and it’s closer to the beginning than the end.