Michael Molcher on Judge Dredd and The Endpoint of 'Policing by Consent'

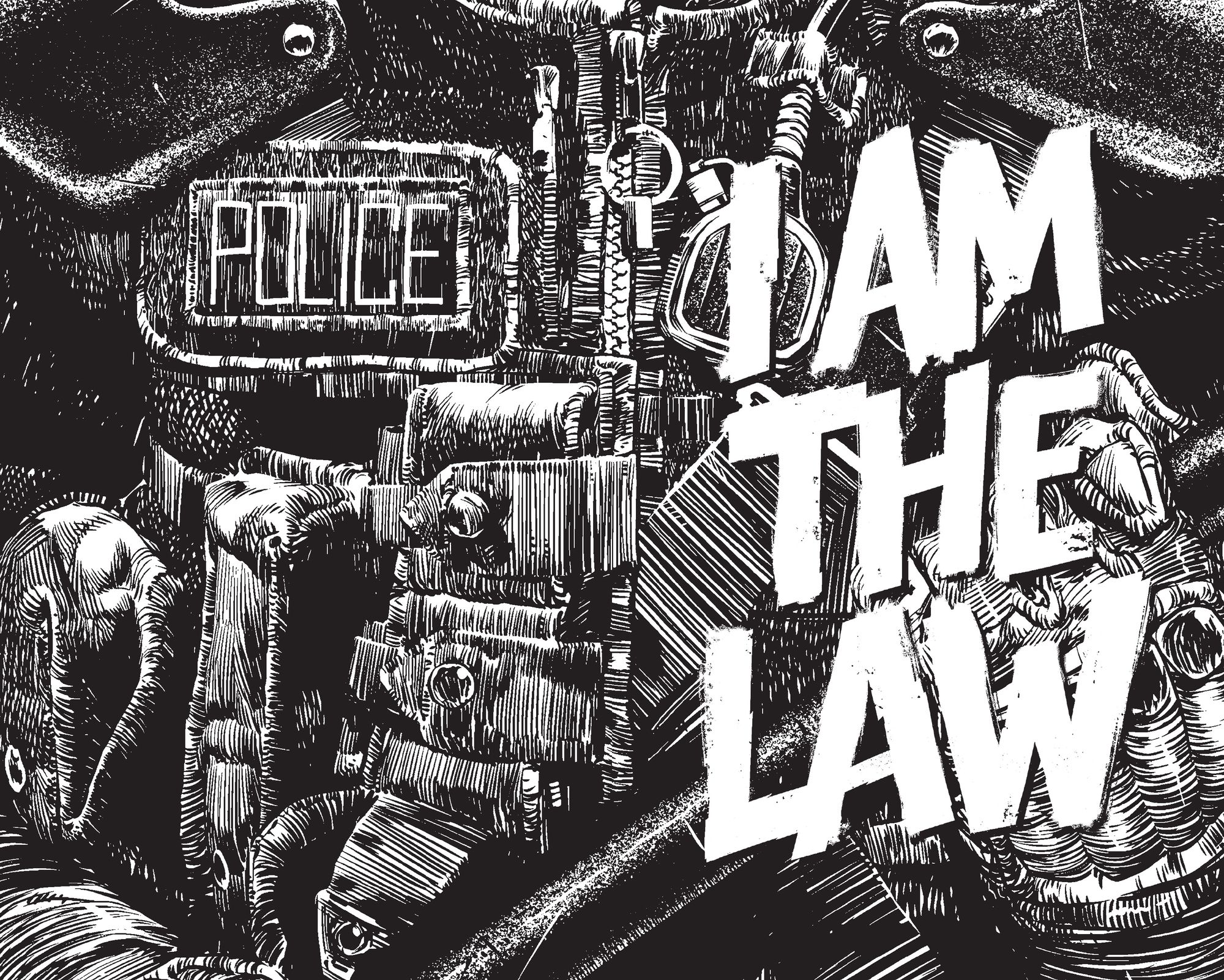

Molcher's new book, I Am The Law: How Judge Dredd Predicted Our Future, is a great one. He speaks to FOREVER WARS about the politics of crime

Edited by Sam Thielman

CAN I CONFESS that I'm, at best, a Judge Dredd casual?

Most of what I know about Dredd comics is Wikipedia-depth: fascist cop in a post-democratic America where he and his ilk decide who's a criminal and deal with them mercilessly. A few years ago, Matt Bors, who knows everything there is to know about Dredd—like, to the satisfaction of a dissertation committee—bought me the America collection. That's got powerful satirical material from John Wagner and Alan Grant, like "Letter from A Democrat," "Revolution" and "Politics." It's great, and it's also where my knowledge of Dredd ends. That and, I suppose, the Sylvester Stallone movie I saw because one summer when I was a teenager my friend worked at a movie theater and let me in.

Also, it seems that the movie forgot that Judge Dredd is a satire. "When some creep's holding a knife to your throat—who do you want to see riding up? Me? Or your 'elected representative'?" is the kind of line that's meant to make you fixate on a knife to your throat, rather than a boot on your neck. (I say it seems like the movie forgot Judge Dredd is a satire because, except for Rob Schneider talking about a Cursed-Earth pizza, I couldn't remember anything in that movie if some creep held a knife to my throat.)

Luckily for me, Michael Molcher, who I was lucky enough to meet at New York Comic Con recently, wrote an absolute ripper of an exegesis on Dredd. I Am The Law: How Judge Dredd Predicted Our Future is a survey and history of modern policing as a replacement for public functions and a means of kettling democracy, all reflected through the visor of a jackbooted sentinel whose world our own increasingly resembles. Equally adept at discussing comics and the work of Giorgio Agamben or Dardot & Laval, Molcher wrote a book that is just extremely my shit. In referencing REIGN OF TERROR, I Am The Law is also nice to me, personally.

Toward the end of I Am The Law, Molcher observes that Dredd creator John Wagner packed his stories full of political, economic and social trauma but refused to provide catharsis. "Many readers find this intolerable," Molcher writes. "In a strip that exists in linear time, the inevitability of death clamors for conclusion, for an end to Dredd. Ultimately, this is the satire of 'Judge Dredd.' Systems of repression are all too aware of their mayfly existence, yet power wants to exist indefinitely. When faced with such a concept, we know that it is unbearable. At his heart, Dredd is intolerable and yet he must last forever. 'Judge Dredd' warns us that the 'law and order' crisis born in the 1970s, which now defines our society and continues to demand ever greater mechanisms of retribution and control, can never end."

If you read this newsletter, I think you'll like I Am The Law. Michael is a comics journalist, award-winning podcaster, and publicist. Formerly a local newspaper reporter and then a government shill—his word!—he is 2000 AD’s brand manager and has written about comics for SFX, Comic Heroes, politics.co.uk, 2000 AD, Judge Dredd Megazine, 2000 AD: The Ultimate Collection and Judge Dredd: The Mega Collection. He lives with his wife and their cat in Oxford and was generous enough to give us an hour of his time during his book's launch week.

Spencer Ackerman: So, Michael, the book is incredible and I want to congratulate you on its success. But I feel like the central question that we have to ask is: When some creep is holding a knife to your throat, who do you want to see riding up?

Michael Molcher: What's so incredible about that line, from Twilight's Last Gleaming, one of the greatest Judge Dredd stories, is that Don Siegel [director of Dirty Harry and The Shootist, among many others—Sam.], in his autobiography that came out in the ‘90’s—just a couple of years after that—parroted exactly the same line when talking about Dirty Harry, which just is the most wonderful, coincidental looping back of history and culture.

I could massively get into the depths of that question, but what you want is Judge Dredd. In that moment, that's the answer that most people would give. As I go into in the book, that's the whole point of law and order politics: to place you in the role of victim.

It's the answer the question is designed to produce.

Yes, at all times, so you're constantly thinking about how insecure you are. One of the great ironies of the politics of crime is that, in discussing security, it breeds insecurity. It makes you afraid and so more vulnerable and willing to surrender your freedoms in pursuit of a security that can never be fulfilled.

In that regard, I wanted to ask you about a concept that hovers around British policing, but which American readers might not be familiar with: What is policing by consent?

Policing by consent is kind of ideological armor that policing has built around itself. It's based on a reading of the work of Robert Peel [A founder of the UK’s Conservative Party and two-time Prime Minister—S.] who created the Metropolitan Police back in 1829, and it's this idea that, rather than the police being a military force that imposes order at the point of a sword, the police are representatives of, and guardians of, and custodians of the King's Peace. It’s the notion that, if a society wants to be secure and safe, and to abide by the rule of the law, then we as a society consent to be policed. And therefore the police must walk a kind of tightrope between enforcing the law and keeping everybody happy. It is, ironically, a concept that the police have really leaned into the more they are engulfed by scandal. They talk about how important policing by consent is, how important the consent of the people is, and it's a myth.

It's a self-generated myth—Charles Reith, who was the great historian of British policing in the 1940s, came up with this notion, based on the writings and speeches and actions of Robert Peel and his successors, as a means of explaining what he saw as the unique characteristic of British Policing—essentially, why we hadn't succumbed to the fascist disease in the 1930s or indeed the communist disease in the 1930s and ‘40s. It's a way of generating legitimacy for the police, so when they do something wrong, they make calls back to policing by consent to indicate ideologically and rhetorically that they are sensitive to the concerns of the people.

But it is rarely the consent of those who are policed that is sought. The history of policing in Britain is very much—it's actually one of my favorite lines in the book—about how Robert Peel, to overcome intense and and long-lasting resistance to the police, convinced the middle classes that [the police] were not there to peer into parlors, but to keep the dangerous classes out of them. That's what policing by consent is. It's the propertied class giving the police permission to police the unpropertied and the undesirable.

How does Dredd both reflect and subvert policing by consent?

Dredd is effectively the endpoint of the kind of rhetoric you get around policing, and particularly in this country, where it's all about the pursuit of order. When he says things like “I am the law” and brooks no argument, and refuses to bend or or be merciful, he is reflecting a liberal view.

That the most important thing is the law, and that springs out of the liberal tradition of the rule of law being the thing everybody abides by and is at the mercy of. But he also shows the ridiculousness of these concepts: The law can be as much an instrument of tyranny as it can of protection. We all love seeing Dredd whack somebody over the head with his daystick and shoot them with his Lawgiver. But the same power that allows him to do that to the people we consider deserving of it allows him to do that to us, as well, and in doing so I think he fundamentally challenges what Stuart Schrader in Badges Without Borders called the illiberalness of liberalism. The police represent the liberal policing order, and the means by which they seek to police us.

What has been the impact of the lack of police unions in the UK? I learned from your book that you don't have them, and ours are a powerful insulation from democratic accountability, which is supposedly the thing that generates this consent. (Read Adam Serwer's essay collection The Cruelty Is The Point for much more on police unions.)

I mean that's a really fascinating difference between our two systems. For those who don't know, the police were banned from having unions after a couple of strikes in the 1910s and 1920s, when the state realized that its enforcement arm could bite back, which it didn't particularly like. So what developed instead were a series of quasi-statutory bodies, like the Association of Chief Police Officers. But primary amongst them is the Police Federation, which is meant to articulate the views and viewpoints of rank-and-file police, but from the 1970s, with the rise of law-and-order politics, became, effectively, a police lobby group. There were various strident chairmen of the Police Federation who talked about how all protesters were fanatics, and they began to to effectively work with the Conservatives—the Tories—in the 1970s to undermine the Labour government of the time. The Police Federation continues to be a very strident and often a disproportionate voice within the media landscape. Quite often, the Police Federation will talk about the home secretary not having the confidence of the police, effectively passing judgment on elected officials.

There's been a wider back and forth over accountability within the police. I explore in the book about how getting fired from being a police officer, or being a police support officer, is actually a lot more difficult than it should be. The Met is currently trying to clean house of all the officers who've got convictions or been arrested for domestic abuse and sexual offenses. But people have been allowed to slip through the net because of the pursuit of policing quantity over quality. So while we've not necessarily got the exact same situation in Britain as the awful situation you do in the States, it's not much better, I think, and whichever political party is in control, because of decades of law-and-order politics, is automatically in hock to the police. And that creates difficulties about holding the police, and the expansion of their powers to account.

You point out that Dredd has little internal monologue. Is that a necessary narrative choice for a satire? Or could you give Dredd interiority without risking turning him into a protagonist and making his works seem like a template?

Oh, that's a really good question. I think Dredd has to be something of a blank slate, or at the very least a mirror, because ultimately, in order for him to work, you need to know as little about him as possible. Don't get me wrong. There has been a kind of internal monologue, where you’re hearing Dredd’s thoughts, but told to you by somebody else, which is much more in keeping with the noir influences on [Judge Dredd creator] John Wagner's writing. Dredd is the fixed point around which the strip turns. if you know too much about what's going on in his head—and it's arguable whether there is much going on in his head, beyond what he does—I think that would ruin it. I'm going to draw on the Impulse comics from the 1990s, where [Mark Waid’s Wally West] talked about the single synapse theory: From thought to deed without anything in between. To a certain extent, Dredd’s like that. What you see on the surface is everything. There is a man utterly dedicated to his duty who doesn't think too deeply.

There's a triptych of stories that begins with “A Question of Judgment” where Dredd consults his mentor, Judge Morph, about the fact that he was chasing down a perp and shot him dead. He goes “Well, I could have disarmed him. I'm good enough with my Lawgiver that I could have, you know, shot his hand and knocked the gun out of it.” And Morph says “If you think about this stuff, it'll drive you insane. So I recommend that you do what I did, which is I got boots a size too small and I spent so much time cursing those boots, I don’t have time to think about anything else.” And at the end of the story Dredd just goes to the kit store and gets a pair of boots that are too small, and so “tight boots” becomes this metaphor for not-questioning, always being focused on the micro, never considering the macro.

Just as a piece of writing, it’s, what, six pages long and effectively sets into motion decades of almost glacial character work. To come back to your question, I think ultimately the less you know about what's going on in his head, the better because he is both a blank slate and a mirror to the world that happens around him.

What are the economic foundations of Mega City One? Does Dredd have a critique of capitalism that predicts our future in an economic sense as well as a political/security sense?

It’s actually part of what I think has made Dredd so enduring as a satire, because at the beginning of the strip 800 million people live in Mega-City One and there’s 97% unemployment because of mass automation. You have semi sentient robots in the strip, they're an incredible device for humor and irony because they're sentient enough to be unhappy with their lot, but not sentient or free enough to do something about it. So they are effectively this mass slave class. And what jobs there are are menial and demeaning, and so you get people who are human furniture or shop mannequins and bed testers. And you know, Dredd himself. I think he's actually one of the best critiques of the capitalism that we're ending up with, where automation has not freed us from the drudgery of work—it's exposed us to the horrors of worklessness and of course you know these stories were being written at the height of the Thatcherite recessions, with 3.4 million people unemployed in a country of between forty and fifty million. It's absolutely fascinating to look back at these things.

On the other side of the coin, what is the role of democracy in Dredd? It’s a thing that I couldn't quite tease out from my, I reiterate, limited exposure to Dredd from the comics, and now through your book. Are the people blamed for Mega-City One?

Effectively what happens is, and I realize this is going to sound very on the nose, the vice president concocts a plot to take over and becomes president. His name's Robert “Bad Bob” Booth, and he's portrayed in different ways in the strip. He goes from being a kind of Nixonian technocrat through a kind of Reaganite tubthumper up to and including a George Bush kind of redneck, Texan-style belligerent warmonger.

So, you've just described Dick Cheney, but please continue.

For various reasons he sparks a nuclear war, feeling safe and secure in the knowledge that America has these vast laser shields that can knock ICBMs out of the sky, and America is has developed into this hyper-urbanized state riven with crime and gang activity. And the Judges are like, “Well, I mean he's in charge. He's following the law so there's nothing we can do about it.” And they discover that it's not quite as plain as that, and they depose him. They invoke the American constitution and they remove him from office, and then they take over and that then continues for years and decades, and democracy is hollowed out. it becomes a circus. There's a mayor and there's a city council but they're mostly concerned with graffiti.

The democratic space constricts tremendously.

Absolutely. And becomes a parody of itself. So you get parties like the Lib-Lab-Flab coalition and the Simps who are both a lifestyle and a kind of political party, as a response to a kind of future shock.

I feel it.

There’s the Apathy Party. Their slogan is “I couldn't care less.” At one point the city elects an orangutan to be mayor in a kind of populist wave. For Mega-City One, democracy is meaningless. It doesn't really connect with people's lives. One time that [problem] actually becomes serious is after there's an event called Necropolis, where the Dark Judges, who are these alien super-fiends from another dimension where all life is a crime, nearly take over the city and Dredd returns and and saves the city and then he realizes that the Judges’ legitimacy has been damaged. We have always vowed to protect the people and we failed so we need to reinvigorate our mandate so they hold a binary referendum. It's democracy or the judges, and of those who vote, the vast majority pick the judges.

That should lead in pretty well to, I think, a good place to wrap this up. You write that Dredd sees himself as above politics he didn't take sides. He wasn't political. He only restored order.

Mm-hm.

How important is it for Dredd and the other judges not to see themselves as practicing politics? And how does that point to a vision of the future that leaves democracy behind?

Well, for our contemporary police, law and order is always framed as apolitical. The police have always framed themselves as apolitical. “We don't take sides. We just stand between the different sides.” But of course the police are agents of the status quo, and for Dredd, order represents that which exists now. You know, the way things are now.

He talks a lot about it. He says, “You know, I'm all for rights, but not at the expense of order.” There’s a famous quote from the Police Federation in the 1970s: “What is political about crime?” The police are always positioning themselves as not taking sides. “We just want people to behave themselves.” Well, you are taking sides, because that benefits existing hierarchies and existing ways of doing things, and Dredd’s exactly the same. I think the Judges promote this idea because it undermines questioning. It basically says “No no, no. They're not politicians. They're just keeping things safe and in order.” And that only benefits the judges. Because it stops everybody questioning them and and as soon as Dredd starts to question it as, he falls apart.

There's this wonderful line in the story “Letter From a Democrat,” in which the kid at the center of the story says, “you know, your kind of law is very final.” And what an incredible metaphor for “law and order” politics, this kind of almost Manichaean view of the world. There's either the order that exists, or there can only be chaos. You either behave or you're a criminal. And for the citizens of Mega-City One, and this is the warning at the heart of it all, you know, Dredd stands over his city, and he says, “800 million citizens, every one a potential criminal.” Like what chance do any of those people have when the state is just waiting to hurt them in the name of order?

And is that order, or is it just the status quo?

It’s just the status quo, one which leaves them miserable, unemployed, and prey to the state and to whatever new crazy villain the writers come up with.

ANOTHER WEEK IN 2023, another U.S. military "collective self defense" airstrike in Somalia. This one, U.S. Africa Command says, took place Feb. 21 near Galmudug. By my count, this is the seventh U.S. military engagement in Somalia this year, and it's not even March. According to AFRICOM's press releases, there were 13 such military engagements in all of 2022.

THE RABBANI BROTHERS, survivors of both the CIA black sites and Guantanamo, are free in Pakistan after 20 years in abusive U.S. captivity. One of the Rabbbanis, Ahmed, a taxi driver from Karachi, was known to be the wrong man by his captors, notes Maya Roa of the human rights group Reprieve: "His interrogators knew they had the wrong man but tortured him anyway, and then built a case against him using the false testimony of other torture victims to justify his indefinite detention." Along with Majid Khan, the Rabbani brothers bring the total of freed survivors of Guantanamo and the CIA torture prisons to three men.

Thirty-two men remain in Guantanamo.

COLD WAR WATCH. My friend Nancy Youssef at the Wall Street Journal (Gordon, you're cool too) reported on Thursday that the U.S. is more than quadrupling its military "training" presence on Taiwan. It's really hard to read the timing of her piece—by which I mean U.S. officials' willingness to talk about this—as disconnected from the past week's comments from Secretary of State Antony Blinken that the Chinese are considering helping Russia replenish its military materiel stocks for its aggression in Ukraine.

This doesn't sound like it'll be the last escalation on Taiwan. Leading voices on the congressional right—which is totally not pro-war; the China Cold War doesn't count as starting a conflict; MAGA wills it so—are demanding it. "We need to be moving heaven and earth to arm Taiwan to the teeth to avoid a war," Rep. Mike Gallagher of Wisconsin, who chairs the GOP Congress' new special committee on China, told Ellen Nakashima of the Washington Post after a visit to Taiwan this week. Gallagher wants rapid fielding of $19 billion of arms sales and transfers, mainly b̶a̶l̶l̶o̶o̶n̶s̶ anti-ship missiles and F-16 fighter jets.

Determining the difference between deterrence and provocation is a gamble, as an anonymous U.S. official concedes to Nancy:

“One of the difficult things to determine is what really is objectionable to China,” said one of the U.S. officials about the training. “We don’t think at the levels that we’re engaged in and are likely to remain engaged in the near future that we are anywhere close to a tipping point for China, but that’s a question that is constantly being evaluated and looked at specifically with every decision involving support to Taiwan.”

THE DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY has issued new guidelines for its use of force. Personnel can no longer use deadly force "against a person who is only a threat to themselves or property," in the description of the San Diego Union-Tribune. But DHS doesn't ban outright the use of chokeholds and the kind of carotid restraint Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin used to murder George Floyd. It even authorizes them in circumstances where deadly force is approved. No-knock entries—AKA, home invasions by officers of the law—are even codified under these new rules. Alex Riggins' piece on this for the Union-Tribune is an appropriately skeptical report, so check it out. Real Judge Dredd stuff.

DATA-MINING SOFTWARE FIRM DUALITY adds the former NSA director/Cyber Command commander Mike Rogers to its board. Taxpayers see no dividend despite training Rogers to operate a surveillance panopticon.

SPEAKING OF THE NSA, THE SUPREME COURT on Tuesday rejected hearing a constitutional challenge to the NSA's UPSTREAM surveillance, whereby the agency siphons data in bulk while it transits the internet. The program renders the 4th Amendment quaint, and you can't challenge it.

VLADIMIR PUTIN is suspending Russia's participation in the remaining nuclear arms-control treaty with the United States, known as New START. We're now in a world where the last remaining nuclear constraint is the international Non Proliferation Treaty. And we've moved there in an atmosphere of conflict between Russia and NATO-supported Ukraine. Dan Smith, director of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, commented on Wednesday in a prepared statement:

On the one hand you could say that nothing much has changed. This step was relatively predictable. Russia has confirmed that it does not intend to breach the treaty limits and that it will continue to notify the USA about any long-range missile launches. However, the uncertainty that this step creates may increase the difficulties in relations between Russia and the USA and their respective allies. It may also increase the already significant difficulties of preserving the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, the world’s main barrier against more states getting nuclear weapons.

Meanwhile, Putin set expectations on Thursday for a major modernization—i.e., a giant funding infusion for development and fielding—of Russia's nuclear triad.

EVERY NOW AND THEN, I think about 20 years of American commentators responding to the latest War on Terror atrocity with some variety of this is a big blow to Western credibility. Lurking in the background in these comments is a sense that credibility is an account you can always deposit more back into, and never that it might be a non-renewable resource. That was in my head when I read Liz Sly's Washington Post piece on Thursday pointing out that outside of North America and Europe, there's little patience with the U.S./NATO narrative of the Ukraine war.

Conversations with people in South Africa, Kenya and India suggest a deeply ambivalent view of the conflict, informed less by the question of whether Russia was wrong to invade than by current and historical grievances against the West — over colonialism, perceptions of arrogance, and the West’s failure to devote as many resources to solving conflicts and human rights abuses in other parts of the world, such as the Palestinian territories, Ethiopia and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

As Sly points out, South Africa's largest export market is the United States. I would add that the U.S. and the UK are principal benefactors of a brutal Kenyan security apparatus post-9/11. These are legacies of history the west prefers to think of as a closed chapter. But those to whom that history happened, to include their descendents, might take a different perspective on the relevance of that history. Expect that perspective to be, once again, a major headwind to the U.S.' current inclination to divide the world into neo-Cold War blocs.