Rudy Giuliani Was A Creation of The New York Media

This is for every New Yorker who in the 1990s watched our local press launder a racist authoritarian mayor into someone who'd save the city from… the people who live here. He always was who he is now

Edited by Sam Thielman

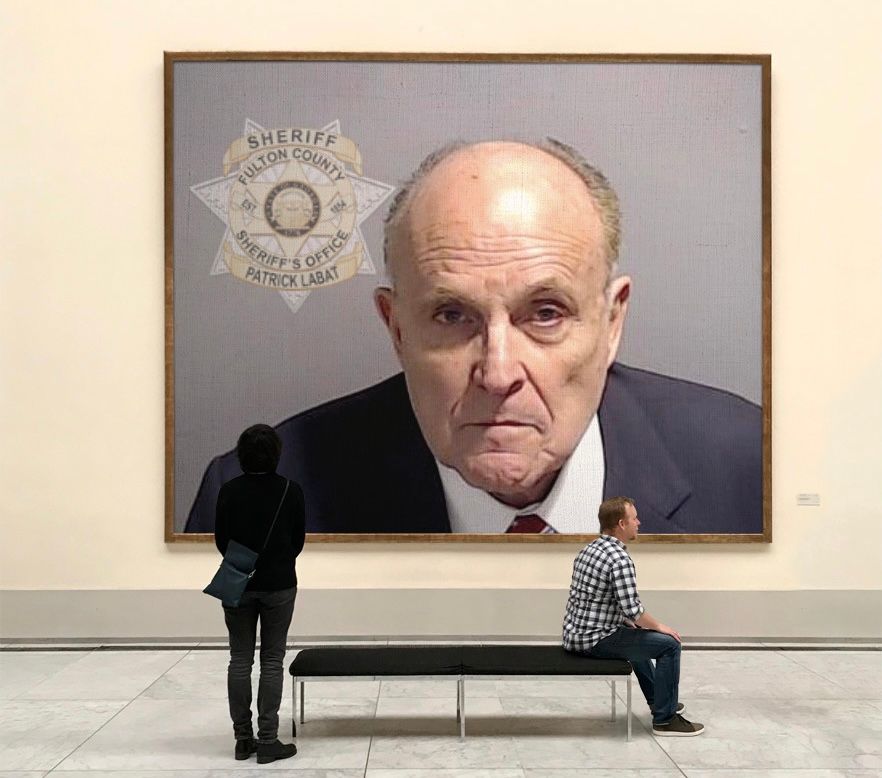

AS RUDY GIULIANI, MAYOR OF THE NEW YORK OF MY YOUTH, surrendered himself in Fulton County, Georgia on Wednesday for his role in attempting to steal the 2020 presidential election, I recalled the New York Times editorial page of October 27, 1997. "Re-elect Mayor Giuliani," it advised its hometown readers.

Sure, the Times readily conceded, Rudy's accomplishments in his brutal first term were "subject to caveats"—most importantly that crime rates in the 1990s had dropped nationwide, not only in New York, despite Rudy taking credit. But while Mayor Giuliani was self-mythologizing, he was ultimately incorruptible. As mayor, the East Flatbush native turned distinguished ex-federal prosecutor was valiant enough to take on racketeering in entrenched baronies like the Fulton Fish Market and the Hunts Point Produce Market in the Bronx.

Beyond the material impact of the Giuliani Era was the vibe. He had brought New York back. Rudy's "combative temperament" was what an ungovernable city needed, "a bit like nuclear fission" in its volatility. Above all, Rudy led the city to what the Times cheered as "a higher expectation of civility." The Times editors endorsed his reelection "enthusiastically."

On August 9, 1997, not three months before the Times draped Rudy Giuliani in its respectability, police from Brooklyn's 70th Precinct arrived at Club Rendez-Vous, a Haitian nightclub on Flatbush Avenue, in response to a scuffle outside between two women. One of the responding officers, Justin Volpe, the 25-year old son of a prominent NYPD detective, took a punch in the fracas. Volpe incorrectly blamed a man named Abner Louima, who had gone out that night to see one of his favorite bands, the Haitian group Phantoms. I don't need to print the word you already know Volpe and his colleagues called him.

Volpe and two other cops, Thomas Bruder and Thomas Wiese, punched the handcuffed Louima in their squad car. When they got to the 70th Precinct station on Lawrence Avenue, Volpe took Louima to the bathroom, grabbed a stick—in some accounts, a broomstick; in others, a plunger—and sodomized him with it. A fourth cop, Charles Schwarz, held Louima down. Then they stuck the befouled stick into Louima's mouth, demonstrating the higher expectation of civility the Times saw in Giuliani's mayoralty.

“I told [Louima], ‘If you tell anybody about this, I'll find you and I'll kill you,’” recalled Volpe in 1999 when he pleaded guilty to the attack in federal court.

Club Rendez-Vous doesn't exist anymore. But it was a few blocks away from where I grew up and where I still live. The police torture of Abner Louima by the 70th Precinct was a signal event for Flatbush, especially for Haitian Flatbush, which in the 25 years since the attack has achieved a measure of elected political power that it conspicuously lacked back then.

I WILL NEVER FORGET THE SUMMER OF 1997. If the reports of Louima's torture hadn't been enough, the photographs of a gaunt Louima, handcuffed to his hospital bed after undergoing intestinal surgery for his wounds, made the NYPD's depravity the talk of the neighborhood and the entire city. The NYPD closed ranks around Volpe, Wiese, Bruder and Schwarz. In response, I started going to demonstrations, which was about the only thing a teenager could do. The biggest of them featured many of us raising plunger handles as we marched up Flatbush Avenue and across the Manhattan Bridge to City Hall, yelling things like The 70th Precinct Smells Like Shit. (I was actually robbed at that protest while we crossed the bridge, but the people who did it got shamed by the crowd and returned my wallet; true story, but for another day.)

Not even Giuliani, knowing the way the winds were blowing, could refrain from criticizing the assault. Louima initially said that the cops told him, "This is Giuliani time, not Dinkins time," but later retracted that, something the mayor's supporters made a lot out of. But the central context of Louima's torture was that Giuliani had unleashed the NYPD on black and brown New York, including with explicit criminological arguments for arresting people for minor infractions, known as "Broken Windows" policing.

During a 1994 New York Post forum on crime, new mayor Giuliani infamously defined freedom as "the willingness of every single human being to cede to lawful authority a great deal of discretion about what you do," while going on similarly authoritarian tangents about how "we're not even sure we share values" as Americans anymore. The year before, a landmark official panel, known as the Mollen Commission, revealed entrenched patterns of "brutality, theft, abuse of authority and active police criminality" within the NYPD and recommended the creation of an independent outside monitor with the power to investigate the cops. That was absolutely intolerable to the police. Giuliani rejected the monitor while praising the commission, a not-particularly-subtle move, but one subtle enough to produce credulous journalism about Rudy's pledged "thoroughgoing effort to root out corruption" in the NYPD.

There was no excuse for anyone writing about Giuliani, at that time or afterward, to be credulous. Giuliani's path to the mayoralty, after losing it in 1989, ran through his grabbing a bullhorn to encourage a racist police riot on the steps of City Hall in 1991. In 2016 my colleagues at the Guardian and I did a retrospective on what has revealingly become an apocryphal event in the city's history—revealing because it tells you who writes the history of this city and what their concerns are—that involved interviewing my childhood city councilwoman, Una Clarke, who was at City Hall that day. I don't need to print the word you already know the NYPD called her. "At the City Hall demonstration, at least one Giuliani supporter circulated through the crowd handing out voter registration cards," the Times reported at the time. It would be ancient history in the newsroom by 1994, and mentioned not at all in the 1997 edit-board endorsement.

What was mentioned in the endorsement? What was front of mind to these editors that crowded out the brutality that Louima's torture had made so unignorable? This:

New Yorkers no longer apathetically assume that they have to put up with aggressive panhandlers, squeegee men or parks full of makeshift housing encampments. Most residents have an increased sense of control over their neighborhoods, and this is most critical in poorer sections of the city.

I feel confident asserting that Abner Louima and the many others who suffered less medieval—but no less real—forms of NYPD abuse, usually in the poorer sections of the city, probably did not “have an increased sense of control over their neighborhoods.” But these were not the people the New York Times, like the broader journalistic class in New York in the 1990s, were interested in taking seriously. The people they took seriously were those New Yorkers who feared the "aggressive panhandlers" while opposing anything redistributive and necessary to address the entrenched poverty—in one of the richest cities on earth—that occasioned aggressive panhandling. Thirty years later, the fruits of Giuliani's labor include many more "makeshift housing encampments" because of the unaffordable city he and his successors created by governing on behalf of capital. Less mentioned in the Times' 1997 cooing over Giuliani's anti-racketeering efforts at the Fulton Fish Market and Hunts Point is that those efforts specifically attacked organized labor.

The New York media's relationship with Giuliani was not outwardly fawning and featured the performance of skepticism. They scrutinized and published treatises about his incorrigibility. Their discomfort intensified as Giuliani grew bolder. He pulled stunts like trying to change the city charter to stop a political enemy from becoming mayor if Giuliani won an anticipated Senate bid, and that provoked backlash. But most journalists treated Giuliani's incorrigibility as a feature of his political appeal, necessary for his great works. With the exceptions of real ones like Wayne Barrett, they tended to portray his authoritarianism, openly discussed as such, as an operatic joke, Rudy being Rudy. As so much of the national press lives in New York, it followed the local media cues about Giuliani. Narratives are made by such things.

David Swanson at Talia Lavin's place saved me much of the trouble of compiling a sampling of Giuliani's coverage as mayor and, before that, during his star-making turn as U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York. The contempt for his clownishness and the pearl-clutching about his brutal methods are all there, but ultimately Rudy is not the villain of these pieces. The villain is the New York of those people, who are always ready to reassert themselves and terrorize the virtuous if there isn't a cop on the beat.

Giuliani-journalism fell into predictable patterns, even during an exceptional story like Louima's. Giuliani said he was against the torture of Louima, so there was no need to explore him creating the context for it. The police who did it were always "rogue" cops – never mind the quickly-forgotten findings of the Mollen Commission – and journalists of the era were content to write about rotten apples without inspecting the barrel, the tree or the crop. Even Mike McAlary of the Daily News, who did the pioneering work of breaking the Louima story and following it through, wrote that Louima's abuse "seem[ed] so impossible." He probably didn't ask the family of Anthony Baez, whom police choked to death in the Bronx after a football he and his friends were tossing around accidentally hit a patrol car two and a half years earlier.

If you read and believed what the New York press wrote and broadcasted about Giuliani, you would be well-equipped to cite various details of city governance but poorly equipped to understand the lasting impact of Giuliani's mayoralty. You might not come away with as many stats, but you'd get a better idea of the larger picture by listening to the New Yorkers the Giuliani era placed behind the eightball. Their sentiments were often expressed in contemporary New York hardcore and hip hop, like "Police State" by Agnostic Front or "Mayor" by Pharoahe Monch.

Giuliani got away with all of it and, like most megalomaniacs who get away with stuff, scaled it up. It was an ironic demonstration of who Broken Windows does and doesn't apply to. You can read REIGN OF TERROR for the apotheosis of Rudy as a national hero after 9/11, another example of credulous mythmaking.

Very often for the last decade it has felt like the hometown villains of my youth—Rudy, Trump—have gotten stronger and swallowed the country. This is New York, and our outsize influence on American media, finance and politics has real consequences. Rudy Giuliani was only able to do the damage that he did, whether in 1994 or 2020, because of the permissive-to-fawning treatment he consistently received from New York journalism. I have no patience with Trump-era questions from journalists about What Happened To Rudy. Rudy told anyone willing to listen who he was in 1991 when he yelled "bullshit" into a bullhorn at City Hall, encouraging the police as they made their drunken, violent assertion about who really runs this place. He told us again and again for 30 years, with only the scale of his ambition changing. The tragedy and the betrayal of my chosen profession is that its incentives usually encourage us to be the last ones to listen.

ONE LAST THING ABOUT GIULIANI, one that I couldn't fit naturally within the above narrative but has to be mentioned. Yes, Giuliani told us who he was in 1991. But he also told us who he was in 1982, when, as an appointee in the Reagan administration Justice Department, he rejected the asylum claims of thousands of Haitian refugees fleeing the American-backed tyrant Baby Doc Duvalier. He met personally with Duvalier and declared there was no political repression in Haiti. The result was the "placement of thousands in detention camps; incarceration of women and children; [and] splitting up family members." Giuliani's actions foreshadowed both the War on Terror and the Trump administration. And it happened before Giuliani's career-making appointment as federal prosecutor in Manhattan.

I can't read Kreyol. But I guarantee that Flatbush's own Haiti Progres outperformed the major New York papers in understanding and portraying the Giuliani mayoralty.

LONG AGO, I USED SONG LYRICS EXCLUSIVELY AS TITLES FOR MY BLOG POSTS. This was a psychotic and self-defeating thing to do but once I started doing it I did not stop for years—which, unfortunately, is extremely on-brand for me. All that is to say I deserve recognition for the personal and professional growth I have demonstrated by not headlining this piece "Giuliani, Giuliani, Giuliani, Fuck You, Die" despite the news granting me the perfect opportunity. [So recognized.—Sam]

RIP BOZO. Never half-measure a coup and then fly in airspace controlled by the guy you didn't overthrow who kills people for a whole lot less.

CUSTOMS AND BORDER PROTECTION bought an AI tool from a totally-not-bullshit company that purports to measure "sentiment and emotion" in social media posts and use that – again, in a totally-not-bullshit way – to map threat networks that, I repeat, are totally not bullshit. That's a new report from Joseph Cox at the worker-owned post-Motherboard site 404 Media that's worth checking out.

ONE LAST THING NOT ABOUT GIULIANI. Tom Shachtman, father of fancypants Rolling Stone editor Noah, is an accomplished writer in his own right. He's out this month with a brand-new novel, Echoes, or, The Insistence of Memory. I haven't had the chance to read it yet but here's a description:

Ell, a millennial of European and Mexican heritage, has one humorous children’s book published, but her more serious writing projects are stalled, her boyfriend has dumped her, and she is deeply frightened by a recurring dream. To solve her problems, she delves into family mysteries—Civil War-era slaveholding, madness, and theft of artifacts. The key to all, previously unknown to Ell but remarkable, is a female Confederate warrior ancestor whose nightmare echoes her own. By tracing both of their dreams to ancient times, and by using insights from modern genetic theory, Ell solves the mysteries and enables herself to move forward.

Get Echoes at the link above or wherever fine novels are sold.