Science Fiction Land

What happens when the theme-park guys come for Jack Kirby and Chloe Zhao

WHEN IT COMES to the big multiplex-hogging Marvel and DC films, the movie adaptations of comics are often divorced—probably of necessity—from the cultural moments that inspired the source material. Chloe Zhao’s pensive, occasionally gorgeous adaptation of Jack Kirby’s The Eternals both suffers and benefits from this; for all that it has aspirations beyond the trademark MCU quippy dialogue and lore dumps, it simply doesn’t have the conviction of its absurdity. What it does have, gratifyingly, is an artistic sympathy with Kirby. Zhao, more than anybody else who has worked on the Marvel movies, has King Kirby’s eye for the gigantic, and that, at least, is very much worth watching. The cinematic equivalents of Kirby’s vast two-page spreads go a long way toward bridging the gap between Zhao’s conflicted theology (Jeet Heer is good on this) and Kirby’s love of goofy bombast (Jessica Crets is good on that).

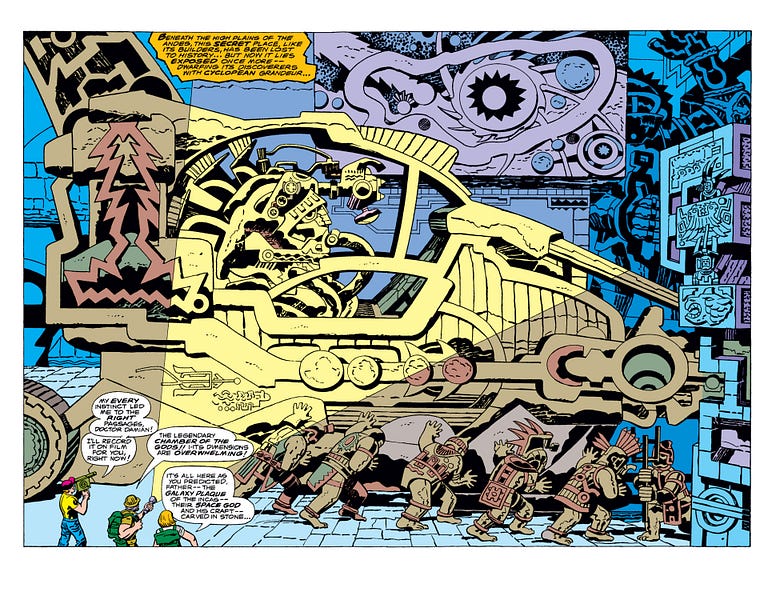

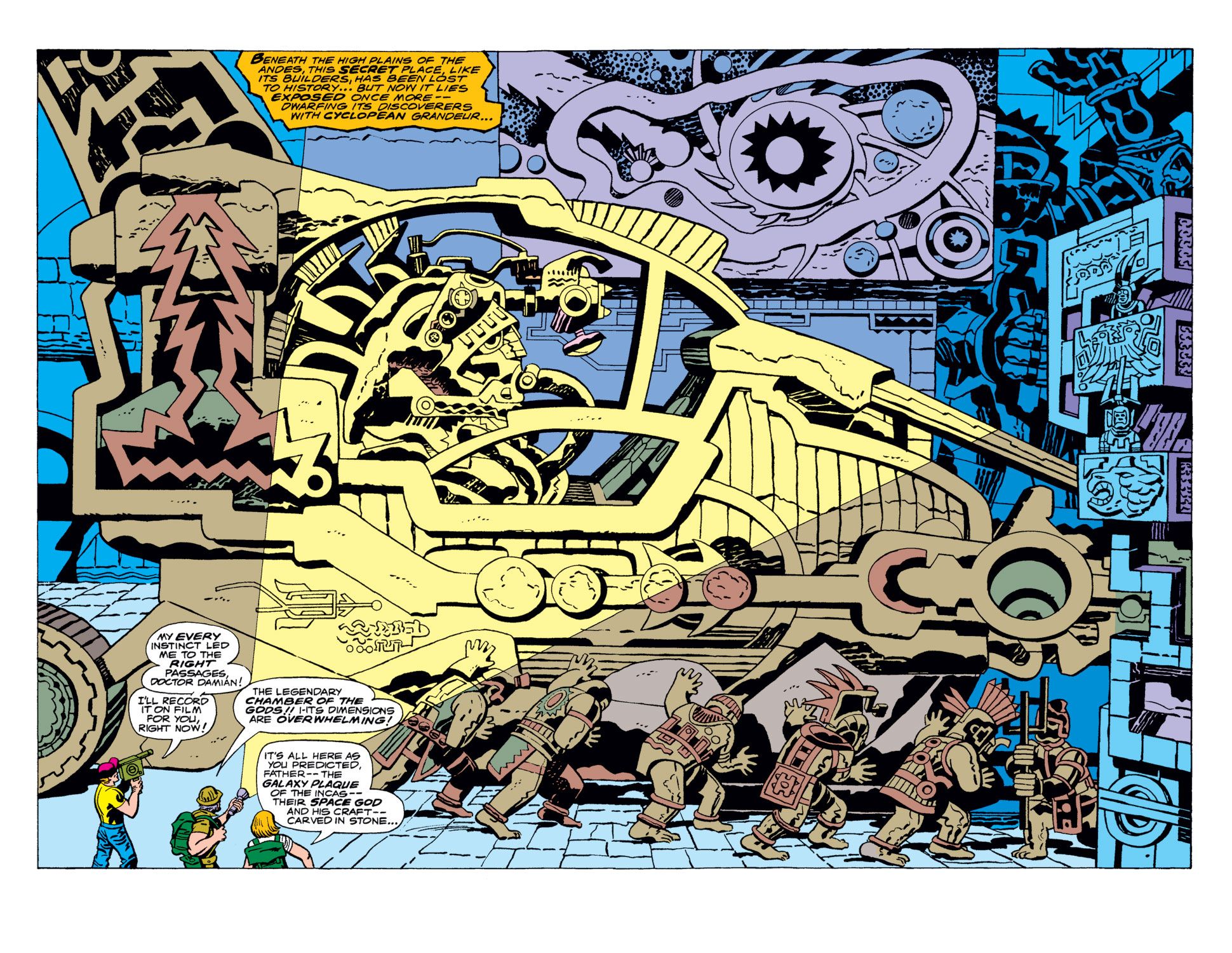

Kirby’s The Eternals was published at a moment of unprecedented baloney, much of which provoked his fertile imagination: “MORE FANTASTIC THAN CHARIOTS OF THE GODS!” bellowed the cover blurb on the second issue, a reference to Swiss author Erich von Däniken’s fanciful, best-selling noodlings about ancient astronauts and the “unsolved” mysteries of archaeology (the book was, to Däniken’s credit, properly titled Chariots of the Gods?). In The Eternals, Kirby posited a three-way conflict between humans, caught in the middle; the demonic Deviants, who are each a species of one; and the angelic Eternals, who can neither die nor reproduce and protect humans from Deviants. The twist is that the real villains are the Celestials, who created all three races to be more or less disposable—a theme Neil Gaiman would expand on and make more explicit in his own Eternals miniseries decades later, giving the whole affair a slightly more Lovecraftian feel. The Deviants in particular are pretty sure the Celestials just eat them.

Because of Däniken, Inca- and Olmec-flavored spaceships were the order of the day in 1976’s science fiction, which determined the look of the Celestials in particular. Kirby loved the cross-pollination of theology and sci-fi—he had already written New Gods and its companion titles for DC Comics, and his next projects would be an ongoing series based on Stanley Kubrick’s elliptical adaptation of 2001: A Space Odyssey and huge sets for a never-to-be-made movie version of Lord of Light by Roger Zelazny. None of the projects were realized in a way that satisfied Kirby; his shocking, eccentric art was roundly panned as self-parody, though that opinion has changed since his death. Lord of Light in particular was the kind of fiasco that is almost too perfect a microcosm of the way the film industry treats great artists.

You’re reading a free post by Sam Thielman on FOREVER WARS, an independent outlet devoted to covering crimes of the state. We can’t make this work without support from our readers, and we want to keep on doing it as long as there are crimes to investigate (hence the title). Please consider signing up for a paid subscription using the button below.

In all of these projects, human beings must reckon with the idea that huge implacable industrial-theological forces are arrayed against them; you can be forgiven for seeing The Eternals as a repository for Kirby’s spare Fourth World ideas, including one hilarious panel in which the Eternals themselves rescue the ark of Genesis from the flood (and the deviants), but they are also the work of a guy who spent most of his career getting screwed out of the rights to his work by richer men with better lawyers. The smallness of people caught in a big, hopeless machine is also perfect territory for a filmmaker with Nomadland director Zhao’s preoccupations; Gemma Chan plays Sersi, the movie’s protagonist, with a kind of sadness I don’t think I’ve seen before in the Marvel films. At first, it is fueled by her huge responsibility to her godlike masters, then it becomes her equally somber responsibility to defy them and to convince her friends to do the same.

I’m frankly as surprised as anyone to see myself writing about this particular space-monsters-and-fashion-models film as though it contains recognizable human emotions, but I’m forced to admit that it does, even though quite a few of its shared-universe predecessors definitely do not. (Nor does the source material, frankly; the art is beautiful but about 80 percent of Kirby’s sentences end in exclamation marks.) In structural terms, Zhao pretty much destroys the movie by adding in all the scenes necessary to graft on real human feeling, but they make its climax something if not unique, then rare in the Marvel pantheon. The real people-eating monster, one suspects, is the Elder Gods of the Walt Disney Company, its DoD contracts, action figure licenses, and theme park attractions corresponding artistically to the value of about one Celestial each. Yes, they have created fascinating wonders and horrors, but mostly as a snack they’re saving for later.

This is the problem with the Marvel movies more broadly, but in Eternals, it’s a problem of two great artists whose work is confoundingly hard to adulterate; several directors within the Marvel stable have made careers out of realizing the company’s TV-on-the-big-screen aesthetic, but they’re generally not the directors who can make universes of their own. Kirby was the same way; the best takes on his characters reverse or deconstruct them, rather than trying to carry on his legacy. Out of Zhao’s hands, the perky signposts for the next megablockbuster feel especially artificial, and out of Kirby’s hands, mystical bullshit is just bullshit.

IN THE CASE OF LORD OF LIGHT, producers Barry Ira Geller and Jerry Schafer proposed to reuse Kirby’s ornate sets as attractions in an unlikely-sounding Colorado amusement park, Science Fiction Land. The conceit was pure Kirby: “Science Fiction Land will offer 2,000 hotel rooms and, after completion, will be tied to Colorado Springs and Denver by a jet-powered transit system, [Schafer] said,” according to an article in the Nov. 19, 1979 edition of the Grand Junction, Colo. Daily Sentinel.

The park, he said, will have a heliport located atop three 10-story statues, with each of the statues housing a major restaurant.

One of the park's major structures will house three children's theaters and a 1,000-lane bowling alley manned by robots who will collect money and give customers their bowling shoes, Schafer said.

Security officers in the park will be outfitted with jet packs developed by the Army and capable of lifting the guards 20 feet off the ground for short distances, he said.

Possibly obviously, Schafer was ultimately tried for securities fraud; angry backers told detectives he had convinced them to invest in his project after misrepresenting the ironclad nature of the Bank of Canada’s interest in the project. An old issue of Starlog aggregates the relevant reporting well. (Schafer had also tried to market a perpetual motion machine, according to a separate Los Angeles Times article, marking one of the few instances when violating an immutable law of physics has carried criminal penalties.)

The theme park and set designs for Lord of Light were scrapped after the movie project evaporated. They proved useful to the CIA, however: The agency acquired them without paying Kirby for them through Lord of Light and Planet of the Apes makeup artist John Chambers, who occasionally crafted disguise kits for the CIA’s head of technical services, Tony Mendez. Mendez used Kirby and Mike Royer’s fantasy drawings (and Schafer’s pre-arrest press clippings) to give an air of authenticity to a dummy movie production company he used to carry out what would become known as the Canadian Caper. You can see some of the designs here.

The movie about the fake movie, Argo, won three Oscars, including Best Picture. Erich von Däniken’s theme park opened in Interlaken in 2003.