Yes, Why Not Let Abu Zubaydah Testify?

On one hand: The CIA might not be able to get foreign spy services to torture people. On the other: A tortured man could pursue justice. 🤔

Edited by Sam Thielman

Buy REIGN OF TERROR: How The 9/11 Era Destabilized America and Produced Trump

SOMETHING UNEXPECTED HAPPENED in the Supreme Court on Wednesday. Not only did the justices express a very belated skepticism toward impunity for CIA torture, one of them in particular showed a lack of familiarity with the reality of the War on Terror.

Zayn al-Abidin Muhammad Husayn has been a captive of the United States for 19 years. His first jailers were the CIA, which made him a human experiment for its theory of cooperation through “learned helplessness”—physical and psychological torture. Since 2006, after the CIA withdrew its contention that he is a member of al-Qaeda, Husayn’s jailers have been the U.S. military’s Task Force Guantanamo. At Guantanamo Bay, he faces no criminal charge and no likelihood of one. A habeas corpus case to free him from Guantanamo has been useless. When Husayn is not forgotten outright, he’s treated not as a man but as a nom de guerre: Abu Zubaydah.

Abu Zubaydah’s attorneys have, practically speaking, one avenue for justice available to them, and it’s tellingly foreign. In 2015, the European Court of Human Rights found that Poland was one of the countries that hosted the CIA torture of Abu Zubaydah. That discovery reopened a criminal investigation in Poland into complicity in his torture. Since the U.S. government gags Abu Zubaydah at Guantanamo Bay, his lawyers sought to subpoena the psychologist-architects of CIA torture, contractors James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen, to introduce evidence about what actually happened to him in Poland.

But the Trump Justice Department asked a federal court to prevent the testimony on the grounds that Mitchell and Jessen would be disclosing state secrets. Last year, a divided Ninth Circuit appellate court narrowly ruled that the lower court, rather than summarily dismissing Abu Zubaydah’s subpoena request, needed to distinguish between what was a genuine state secret and what isn’t. Earlier this year, the Biden administration took up the Trump administration’s petition that the Supreme Court should stop that from happening—and, by the transitive property, stop Mitchell and Jessen’s testimony to the Polish prosecutor.

There is a long post-9/11 record of judges dismissing cases once the government invokes a state-secrets provision. That record suggests that the Justice Department may well prevail again. But during oral argument on Wednesday, the justices showed impatience with an assertion of government secrecy as sweeping as it has been routine. But a leading figure on the court seemed not to understand an extralegal apparatus that he helped legitimize.

WHILE I’M NO SUPREME COURT watcher, it was striking to hear the justices talk about the War on Terror without the veneer of patriotic emergency so typical of the relatively few times that Forever-War operations have been the issue before it.

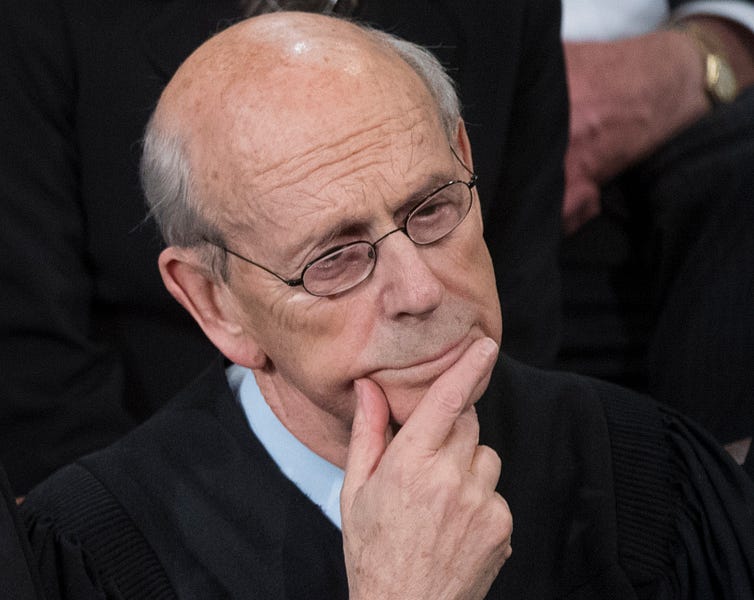

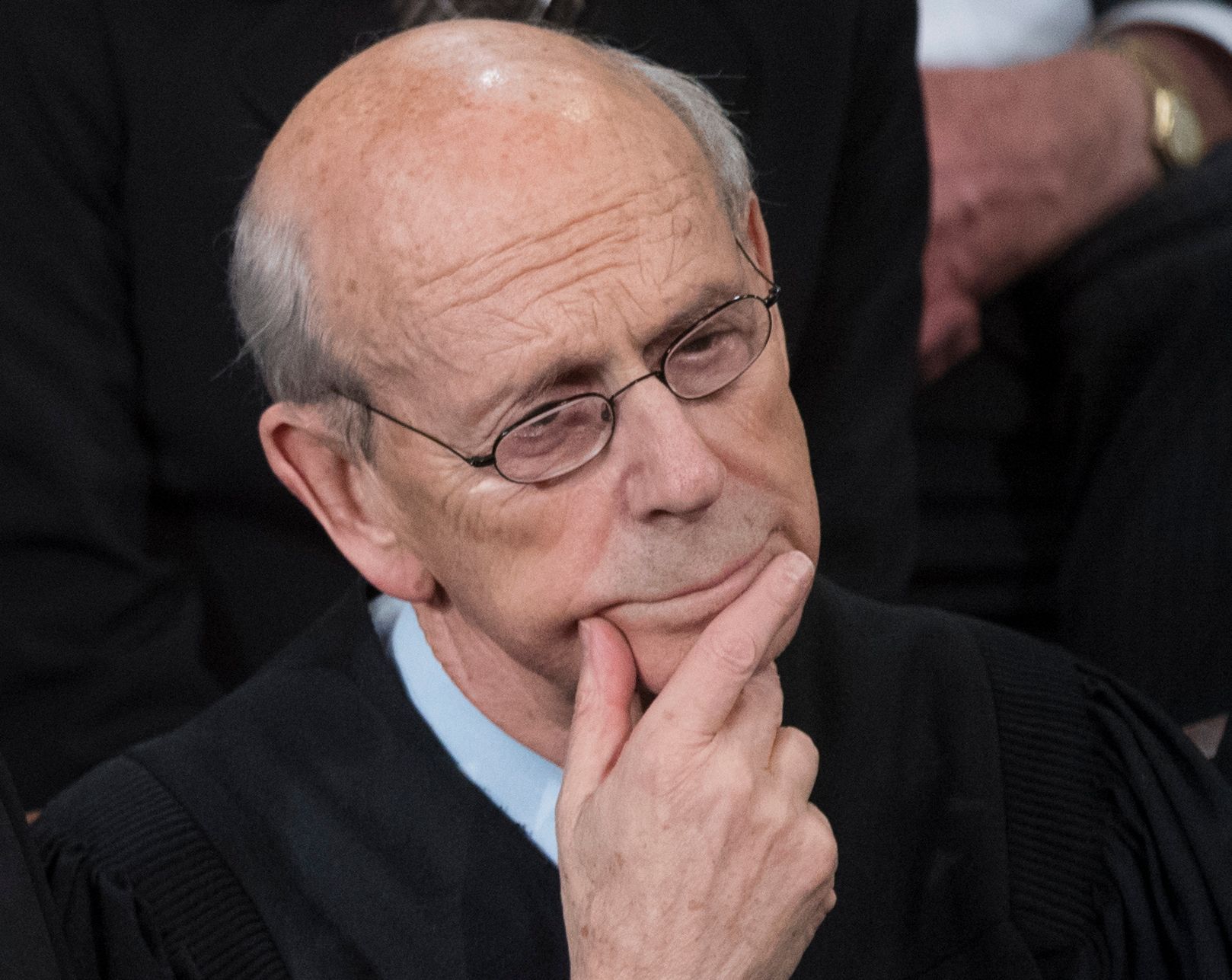

Justice Amy Coney Barrett referred plainly to Abu Zubaydah’s “torture.” Almost as soon as Brian Fletcher, the Justice Department attorney arguing before the court, insisted there was no way to question Mitchell and Jessen without confirming Poland’s involvement in CIA torture, Chief Justice John Roberts interjected, “it seems to me there may be a lot that they can talk about that have nothing to do with the actual location at which events occurred.” Justice Elana Kagan, observing that the contours of what the CIA did to Abu Zubaydah have long been public, remarked, “at a certain point, it becomes a little bit farcical, this idea of the assertion of a privilege, doesn't it?” Justice Stephen Breyer—more on him in a moment—mused that he didn’t understand why any of the Guantanamo detainees remain detained after the Afghanistan pullout, which Biden often rhetorically conflates with the end of the War on Terror.

Questioning Abu Zubaydah’s attorney David Klein, the justices drilled down onto the question of what precisely Abu Zubaydah’s legal team wants out of Mitchell and Jessen. Klein said Abu Zubaydah doesn’t need Mitchell, Jessen or any actual government official to affirmatively confirm Poland’s involvement. For the Polish criminal case to proceed, all Abu Zubaydah needs is someone in the room to explain what the CIA did to him during his 2003 captivity there.

After 20 years, and almost casually, Breyer arrived at the central question.

“Why don't you ask Mr. Zubaydah?” Breyer wondered. “Why doesn't he testify? Why doesn't Mr. Zubaydah—he was there. Why doesn't he say this is what happened? And—and they won't deny it, I mean, I don't think, if he's telling the truth.”

What a circumstance Klein found himself in! He had to gently explain the fundamental post-9/11 reality that Abu Zubaydah faces—a central fact confronting the hundreds who have been held in Guantanamo and the thousands held in military and CIA cages. “Because he is being held incommunicado,” Klein gingerly recounted. “He has been held in Guantanamo incommunicado.”

Stephen Breyer, the leading liberal on the Supreme Court, revealed that he knows not even the basics of the wartime detention apparatus that he, as part of the 6-3 majority in 2004’s Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, blessed. He was also part of the 5-4 majority for Boumediene v. Bush in 2008, a ruling that said Guantanamo detainees are entitled to hearings contesting the basis for their detention—if you’ve ever heard the words “habeas corpus,” this is what that means—yet he also seemed not to know how that has worked in practice.

“I mean, have you filed a habeas or something, get him out?” asked Breyer, a newborn babe who is one of the most powerful people in the United States.

“There has been a habeas proceeding pending in D.C. for the last 14 years,” Klein remarked. It is news to Breyer that the Justice Department, primarily under Obama, vigorously and successfully lawyered away the habeas rights Boumediene acknowledged. No one got out of Guantanamo because of habeas litigation.

I can truthfully say that I once talked to Justice Breyer while I was high on cocaine and this is the wildest he has sounded to me. Bless his heart that he thinks the CIA “won't deny it, I mean, I don't think, if he's telling the truth.” It turns out Supreme Court justices don’t pay any closer attention to a generation-long, democracy-eroding war than any other American elite. The destruction of the rule of law is not visible from the vantage of the highest court in the land.

WHAT THE BIDEN administration has said, and done, about Zayn al-Abidin Muhammad Husayn is significant too.

First, so as not to bury news from the end of a Supreme Court hearing, Fletcher, the DoJ attorney, clarified that the pullout from Afghanistan, in the Biden administration’s view, does not obligate the U.S. to release anyone from Guantanamo. “Notwithstanding withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan, we continue to be engaged in hostilities with Al Qaeda and therefore that detention under law of order [sic, he presumably meant the Law of War] remains proper,” he said.

More fundamentally, the Biden administration could have chosen not to contest Abu Zubaydah’s desired subpoena of Mitchell and Jessen. Making such a choice would have allowed the administration to avoid occupying its current moral position, in which it contends that the right of the CIA to conceal its accomplices, in perpetuity, outweighs any claim to redress made by the CIA’s victims. The Justice Department’s Fletcher led off with precisely this point before the Court on Wednesday: “Our nation's covert intelligence partnerships depend on our partners' trust that we will keep those relationships confidential.”

Helpfully, his boss, Acting Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar pointed to exactly the “national security interest” at stake. In her July filing, Prelogar relied upon assertions from former CIA Director Mike Pompeo, who after all is a notably, eminently trustworthy figure.

At an earlier moment in the case, Pompeo asserted that permitting Mitchell and Jessen to discuss Polish involvement in Abu Zubaydah’s torture could impair the CIA imperative of “a cooperative and productive intelligence relationship with foreign intelligence and security services.” That cooperation depends on the U.S. keeping “any clandestine cooperation with the CIA secret,” Pompeo continued. This imperative is predicated on protecting an allied intelligence service from reprisal if, for instance, “new political parties or officials come to power in those foreign countries that want to publicly atone or exact revenge for the alleged misdeeds of their predecessors.”

It’s worth dwelling for a moment on how expansive that assertion is and what it means in practice. Even if a democratically elected government comes to power that wants “to publicly atone” for a predecessor’s complicity in CIA torture, the U.S. ought to oppose that, and treat it as the equivalent of “exact[ing] revenge.” It further means that hypothetical future cooperation with the CIA that could be hindered by the present-day confirmation of a widely-identified CIA partner is more important than any right Abu Zubaydah possesses. Delving a level deeper, it also implies the absurdity that nations cooperate with the CIA for reasons other than an alignment of interests. The CIA repeatedly shits the bed on protecting its sources – and even its digital arsenal! – and yet, somehow, for reasons I just can’t figure out, the intelligence service of a globally hegemonic power still attracts and maintains bandwagoners.

I mention the Pompeo thing because the Justice Department relies on it extensively. Its brief says that judges must show Pompeo, in his former capacity as CIA director, “the utmost deference... regarding national-security harms.” Before the Court, Fletcher said that “what I'm doing in candor is telling you… some of the concerns that Director Pompeo has identified here.” What Pompeo has asserted, Biden’s CIA Director, Bill Burns, has ratified, according to Prelogar: “The CIA informs this Office that the current CIA Director has likewise determined that the compelled discovery of that information would reasonably be expected to harm the national security and that the government should therefore continue to oppose discovery of that classified information in this case.”

Justice Neil Gorsuch asked Fletcher why the administration won’t permit Abu Zubaydah to testify. He instead took umbrage at Klein’s plain description of the truth: “He is not being held incommunicado. He is subject to the same restrictions that apply to other similar detainees at Guantanamo.” Gorsuch, smelling the bullshit, pressed Fletcher, who finally admitted he had no idea if the administration will permit Abu Zubaydah’s testimony.

“Well, gosh,” Gorsuch replied. “We've been—this case has been litigated for years and all the way up to the United States Supreme Court, and you haven't considered whether that's an off-ramp that—that the government could provide that would obviate the need for any of this?”

THE ONLY REAL RULE of the black sites, and Guantanamo beyond them, is silence. What the CIA did to people there, like what the military did and does to people inside Guantanamo Bay, is to remain secret. Secrecy is impunity’s valet. The CIA understands this. The Justice Department understands it well enough to euphemize it when presenting it to respectable elites like Supreme Court Justices—who, like the respectable elites they are, exhibit “blooming, buzzing confusion” when presented with an atrocity they had long since decreed lawful and then forgotten about.

Joseph Margulies, a longtime attorney for Abu Zubaydah, didn’t argue before the justices. But I asked him about Breyer’s question. To be extremely clear, everything I wrote above is my perspective, not Joe’s.

“Sometimes the plainest truths are the hardest to see, and we're grateful the justices saw what we have pointed out for years: Of course, Abu Zubaydah was tortured,” Margulies said. “Of course, he should be allowed to speak for himself. Of course, his detention is unlawful. We hope the Biden administration gets the message.”

Not to step on that Margulies kicker quote, but I’ve recorded an episode of Law360’s podcast The Term about the Abu Zubaydah SCOTUS hearing that should be released shortly—possibly by the time you read this.